|

Weather Eye with |

El Niño and La Niña are opposite phases of a naturally occurring global climate cycle known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO for short. ENSO influences rainfall, temperature, and wind patterns around the world, including New Zealand. El Niño and La Niña episodes occur on average every few years and last up to around a year or two.

Although ENSO has an important influence on New Zealand’s climate, it accounts for less than 25 percent of the year-to-year variance in seasonal rainfall and temperatures at most locations. Nevertheless, its effects can be significant.

El Niño

During an El Niño event, ocean water from off the coast of South America (near Ecuador and Peru) to the central tropical Pacific, warm above average. The warming takes place as trade winds (the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow around the equator) weaken or even reverse, blowing warm water from the western Pacific toward the east. As a result, sea temperatures in the far western Pacific can cool below average.

The unusually warm water in the eastern Pacific then influences the Walker Circulation, acting as a focal point for cloud, rainfall, and thunderstorms. It is this change in the Walker Circulation that impacts weather patterns around the world.

El Niño’s average influence on New Zealand

It’s important to bear in mind that while we know the average outcome of El Niño because of historical data, no El Niño is average—each comes with a unique set of climate characteristics and therefore can be expected to influence the weather differently.

During El Niño, New Zealand tends to experience stronger or more frequent winds from the west in summer, which can encourage dryness in eastern areas and more rain in the west. In winter, the winds tend to blow more from the south, causing colder temperatures across the country. In spring and autumn, southwesterly winds are more common.

La Niña

During a La Niña event, ocean water from off the coast of South America to the central tropical Pacific cools to below average temperatures. This cooling occurs because of stronger than normal easterly trade winds, which churns cooler, deeper sea water up to the ocean’s surface.

Sea temperatures can warm above average in the far western Pacific when this happens. The unusually cool water in the eastern Pacific influences the Walker Circulation and suppresses cloud, rain, and thunderstorms. This change impacts weather patterns around the world, but in a different way than El Niño does.

La Niña’s average influence on New Zealand

Northeasterly winds tend to become more common during La Niña events, bringing moist, rainy conditions to northeastern areas of the North Island and reduced rainfall to the lower and western South Island. Warmer than average air and sea temperatures can occur around New Zealand during La Niña.

A composite, or average, of the summer pressure and wind pattern during 4 different La Niña events. Areas of above normal pressure are shaded in red while areas of below normal pressure are shaded in blue. [NIWA / data: NCEP]

A composite, or average, of the summer pressure and wind pattern during 4 different La Niña events. Areas of above normal pressure are shaded in red while areas of below normal pressure are shaded in blue. [NIWA / data: NCEP]

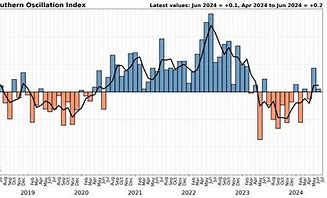

Monitoring ENSO: Southern Oscillation Index

Sir Gilbert Walker documented and named the Southern Oscillation in the 1930s. The clearest sign of the Southern Oscillation is the inverse relationship between surface air pressure at two sites: Darwin, Australia, and the South Pacific island of Tahiti.

Over periods of a month or longer, higher pressure than normal at one site is almost always concurrent with lower pressure at the other, and vice versa. The pattern reverses every few years. It represents a "seesaw" or a mass of air oscillating back and forth across the International Date Line in the tropics and sub-tropics.

The Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) quantifies this pressure difference. Over a period of three months or more, values below -1.0 correspond to El Niño conditions while values above 1.0 correspond to La Niña conditions. Values between -0.5 and -1.0 lean toward El Niño, while values between 0.5 and 1.0 lean toward La Niña. Values between -0.5 and 0.5 are considered neutral.

*******************************************************************************

Neutral ENSO and IOD conditions continue (From Australian Bureau of Meteorology

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is currently (as at early July) neutral.

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the central Pacific have been cooling since December 2023. This surface cooling is supported by a cooler than average sub-surface in the central and eastern Pacific. During June, the rate of cooling has decreased. Cloud and surface pressure patterns are currently ENSO-neutral.

Climate models suggest that SSTs in the central tropical Pacific are likely to continue to cool for at least the next 2 months. Four of 7 models suggest SSTs are likely to remain at neutral ENSO levels, and the remaining 3 suggest the possibility of SSTs at La Niña levels (below −0.8 °C) from September.

The Bureau's ENSO Outlook is at La Niña Watch due to early signs that an event may form in the Pacific Ocean later in the year. A La Niña Watch does not guarantee La Niña development, only that there is about an equal chance of either ENSO neutral or a La Niña developing. Early signs of La Niña have limited relevance to mainland Australia and are better reflections of conditions in the tropical Pacific.

While phenomena such as La Niña provide broad indications of the expected climate, the long-range forecast provides better guidance for local rainfall and temperature patterns.

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is currently neutral, with the latest weekly value close to zero. Predictability of the IOD is low at this time of year, but improves through the winter months. The latest model outlooks indicate that the IOD will remain neutral until at least early spring.

Global sea surface temperatures (SSTs) have been the warmest on record for each month between April 2023 and May 2024. These global patterns of warmth differ to historical global patterns of sea surface temperatures associated with ENSO and IOD; therefore, future predictions based on historical SSTs during past ENSO or IOD events may not be reliable. The Bureau’s long-range forecast provides the best guidance for local climate.

The Southern Annular Mode (SAM) is currently neutral (as of 22 June). Forecasts indicate the index is expected to become positive during late June, before returning to neutral by early July.

The Madden–Julian Oscillation (MJO) is currently weak (as of 22 June) and is expected to remain weak for the coming fortnight, with the possibility of strengthening in the Maritime Continent. A weak MJO has little impact on Australian rainfall.

Average of international model forecasts for NINO3.4 Issued 25 June 2024:

July

SST anomaly: −0.2 °C

September

SST anomaly: −0.5 °C

November

SST anomaly: −0.6 °C

Average of international model forecasts for IOD Issued 25 June 2024:

July

IOD index: +0.2 °C

September

IOD index: 0.0 °C

*************************

For further information on a variety of weather/climate matters see my latest book"Climate Change: A Realistic Perspective".

The title of my recent climate book "Fifteen Shades of Climate" has been changed to "Climate Change: A Realistic Perspective" to better reflect its contents.

I was born in Nelson (New Zealand) and lived in Takaka in 1938-45 when I watched the Takaka River flood, and as a seven-year-old I asked two questions ..Why did it rain, and What were the consequences of the rain. I still have questions, some of which are answered in my book.

The new book is identical to the old book, with the exception that a new Author's Foreword has been included.