“General practice has perhaps done too good a job in protecting the public from the reality of how close we are to collapse.”

That’s the opinion of General Practitioners Aotearoa interim chairperson Dr Buzz Burrell.

New Zealand’s GP-to-patient ratios are “embarrassing”, he says, pointing out that only 25 per cent of practising doctors work in primary care — a stark drop from 40 per cent 10 years ago.

And just a 6 per cent reduction in primary care consultations would double the load on already overburdened emergency departments, Buzz says.

General Practitioners Aotearoa is a membership organisation for GPs in Aotearoa New Zealand launched last year to advocate for the sector after the New Zealand Medical Association was dissolved.

The body wrote to Health Minister Dr Shane Reti on Friday, asking for an urgent meeting to address the crisis in primary care.

GPs are close to industrial action over funding agreements, Buzz says, but they fear that a subtle withdrawal of services would be “catastrophic” for patients and hospitals.

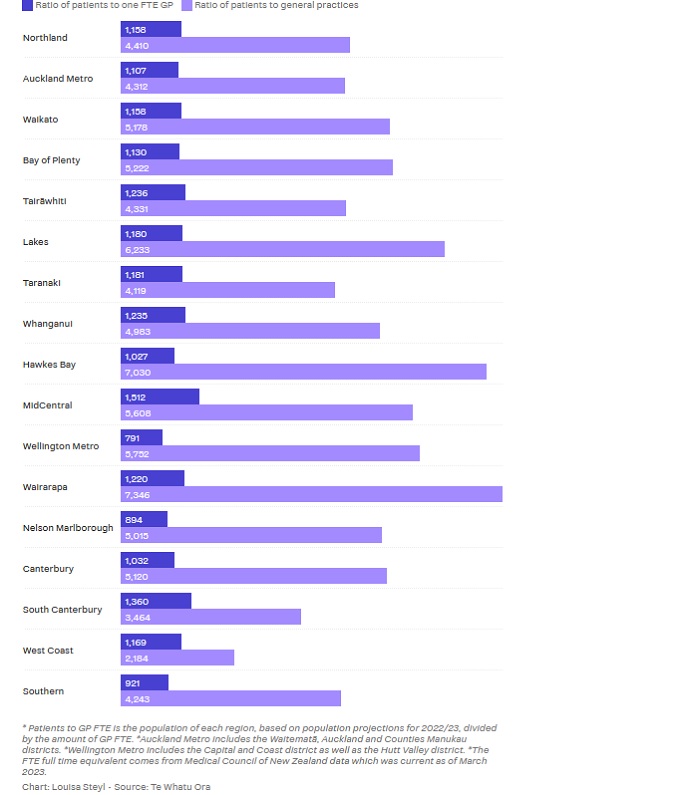

Based on data released under the Official Information Act, Te Whatu Ora puts the average ratio at 1058 patients per full-time equivalent (FTE) GP, or 4767 patients per general practice.

That jumps as high as 1512 patients per GP (94.5 GPs per 100,000 people) or 5608 to a practice in MidCentral, or as low as 791 patients per GP in Wellington Metro; which in this data includes the Capital and Coast and Hutt Valley districts.

These numbers, Te Whatu Ora notes, are based on the 2018 census data updated in 2022, along with the number of doctors registered with the Medical Council of New Zealand as general practice specialists, with FTE based on 40-hour weeks.

Patient to GP ratios around the country

The ratio of patients to full time equivalent general practitioners per district and the ratio of patients served by general practices:

Both Buzz and Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners president Dr Samantha Murton say the actual ratio is higher.

The College’s Future Workforce Requirements Report put the average at 74 GPs per 100,000 people in 2021 — with this expected to drop to 70 per 100,000 by 2031.

Samantha notes that Te Whatu Ora’s numbers could include GPs who work in other roles that aren’t patient facing, like lecturers, or those working in practice management or for a primary health organisation, for example.

In her own Wellington practice, Samantha says two FTE GPs, two FTE nurses, a clinical assistant and a social worker are serving a population of 3,400 enrolled patients.

“We made the decision last year to close our books for the first time since the practice opened. The way current funding works we also have to over work our current staff until we have enough revenue to take on someone new,” she says.

In Australia, the average ratio is 116 GPs per 100,000 while that number is 122 per 100,000 in Canada, Buzz says.

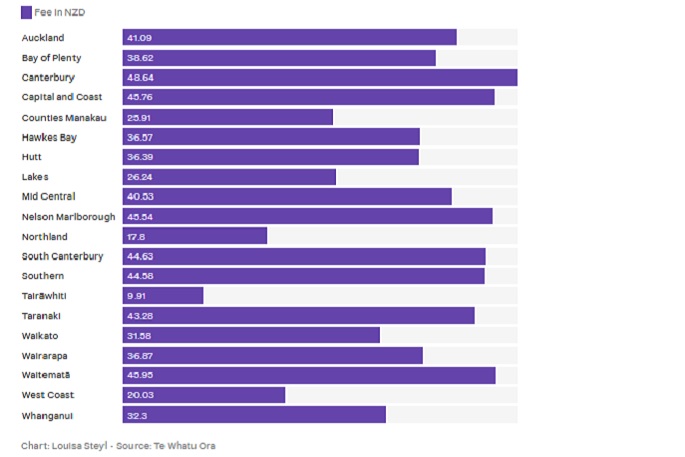

Average adult GP consultation fee per district

Weighted average fees for enrolled adults (18+) patients who don't hold a Community Services Card:

And with more than 100,000 people entering New Zealand annually, Buzz expects the crisis to deepen, costing emergency departments more time and resources.

The average cost of an ED visit that doesn’t lead to admittance was $595 in 2019, for example, when it costs the Government $76.95 if a patient spends 20 to 40 minutes with a GP, he says, while overworked GPs sometimes over-refer to the secondary sector because they haven’t got the time to deal with something themselves.

“Eventually we’ll reach a tipping point and the system will collapse. We’re so close to that.”

So how did we get here?

Buzz is not alone in his thinking. Professor Les Toop, a part-time GP, and former head of the Department of General Practice at The University of Otago in Christchurch told Newsable last year the health system was “the worst it's been” in his 40 years as a health professional.

“We’ve traditionally, in general practice, had GPs retire in their 70s. That's not happening any more, and so the age at which people say ‘that's enough’ is getting lower and lower. And even more worrying, you’ve got people in mid-career who are finding it so stressful that they think there must be something better to do — either go somewhere else or do something else.”

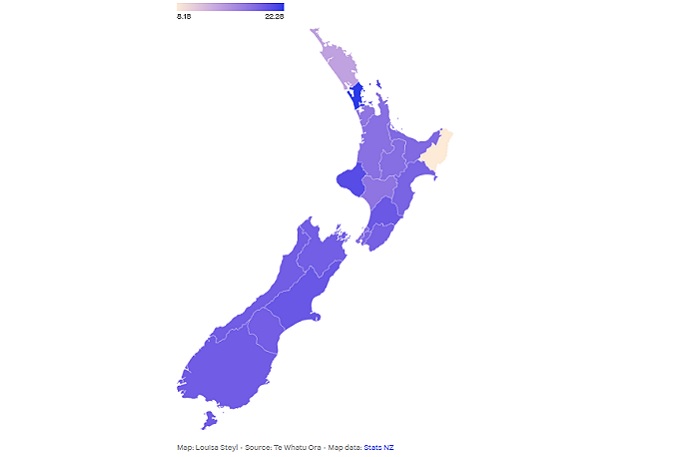

Average cost of a GP consultation for CSC holders

Weighted average consultation fees, in NZD, for enrolled, adult (18+) community service card holders per district:

GPs are facing rising costs to keep their door open, having to pay for everything from staff wages and building maintenance to consumables and registration fees.

With no pay parity for primary care nurses, practices aren’t funded for the higher wages they have to pay to try and hold on to their nurses.

The current funding model was first introduced back in 1941 when GPs struck a deal that would allow them to maintain their autonomy and deliver primary care at affordable prices: consultations would be subsidised by the state.

Doctors could charge a fee on top of the subsidy, but it was rarely needed back then.

But these subsidies haven’t risen with inflation, and GPs are facing increasing costs.

The current funding model is complicated, to say the least, with money coming from multiple different government agencies and distributed based on population factors like the age, ethnicity and financial means of patients.

Royal New Zealand College of GPs president Samantha Murton says the college’s Your Work Counts project is collecting data to show the gap between what GPs do and what they’re funded for. Photo: Robert Kitchin / Stuff.

Royal New Zealand College of GPs president Samantha Murton says the college’s Your Work Counts project is collecting data to show the gap between what GPs do and what they’re funded for. Photo: Robert Kitchin / Stuff.

Te Whatu Ora data, released under the Official Information Act, shows the national average enrolled patient fee is $19.02 for community service card holders and $37.71 for adults without the card.

Cantabrians pay the most, at an average fee of $48.64 a consultation while those in Tairāwhiti pay the least at $9.91 or $8.18 with a community services card.

Buzz says Government subsidies only cover about three GP visits a year and an independent report by Sapere in 2022 found general practice was operating at an annual loss of $137 million nationally.

Some doctors are working 30 to 40 extra hours a week due to administrative tasks, he says, because they can’t afford to do this work during patient hours.

It’s no wonder young doctors don’t want to specialise as GPs, Buzz says.

Dr Bryan Betty, then-medical director of the College of GPs, warns problems will repeat themselves every winter if workforce shortages are not fixed. Bryan is now with General Practice NZ.

How do we solve the problem?

Buzz is calling for serious investment into general practice and a “decluttering” or simplification of the funding model.

“With more resources, more staff, and more time to do the job properly and well, not only is it instantly an attractive career option, but the well-documented health outcome benefits will be seen.”

Samantha also believes there needs to be a focus on growing the workforce locally by supporting registrars and encouraging senior doctors to stay in the profession.

A record 239 medical graduates have started their three-year training programme to become specialist general practitioners through the college this year.

But Buzz fears they’ll head overseas if nothing is done to retain them.

“We need to see our profession valued, and remunerated appropriately, for the significant impact we have on the healthcare of New Zealanders,” Murton says, adding that 90% of health concerns are dealt with in general practice.

Buzz proposes that senior registrars working in hospitals be mandated to spend six months in general practice. It would encourage more to train as GPs, and enhance the skills mix in general practice, he says.

He doesn’t think proposals such as training more nurse practitioners or moving immunisations to pharmacies are helpful, noting that it just means redirecting funds away from practices.

Health Minister Dr Shane Reti says he’s working with the primary care sector and hopes to increase the GP workforce through immigration and training. Photo: Robert Kitchin/The Post.

Health Minister Dr Shane Reti says he’s working with the primary care sector and hopes to increase the GP workforce through immigration and training. Photo: Robert Kitchin/The Post.

“You wouldn’t ask a plumber to do an electrician’s work. It is incredibly annoying to see proposals to address the GP shortage revolving around giving the GP work to non-GPs to do. It devalues what GPs do and comes from a position of offensive ignorance.”

Reti, who comes from a primary care background himself, says a strong primary care sector is essential to providing high quality healthcare.

He is working with the sector, he says, and hopes to streamline processes to make it easier for overseas doctors to immigrate to New Zealand.

But he understands the need to grow a local workforce and is in talks with Waikato University to open a third medical school.

“This, alongside our commitment to increase medical school places, will allow us to train more doctors here at home and provide a long-term, sustainable training pipeline.”

Last week Reti told RNZ he believed primary care was being underfunded.

In December, he told Stuff “urgently addressing issues within the primary health sector” was among his top priorities as the incoming health minister.

1 comment

Hmmm

Posted on 07-02-2024 10:38 | By Let's get real

Maybe the money and resources that could be directed into healthcare is being wasted trying to separate the nation on health issues in parliament.

All we are talking about is skin colour and unsupported belief structures. We are absolutely no different to one another, other than what is in our heads.

We have absolutely the wrong people making money from never-ending debate about health.

But what would we have to do if we couldn't look over the fence at the neighbours and find something to bitch about.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.