Dr Riley Elliot, also known as the Shark Man, will continue tagging great white sharks around New Zealand as early signs indicate the apex predators are returning to Bay of Plenty waters.

The shark scientist told NZME he had received his first report in years of baby great whites at the Bowentown Harbour entrance, a potential sign that the species was re-establishing in the region after the 2023 floods.

In 2022, the Tairua scientist established the Great White Project, which involves satellite-tagging the sharks.

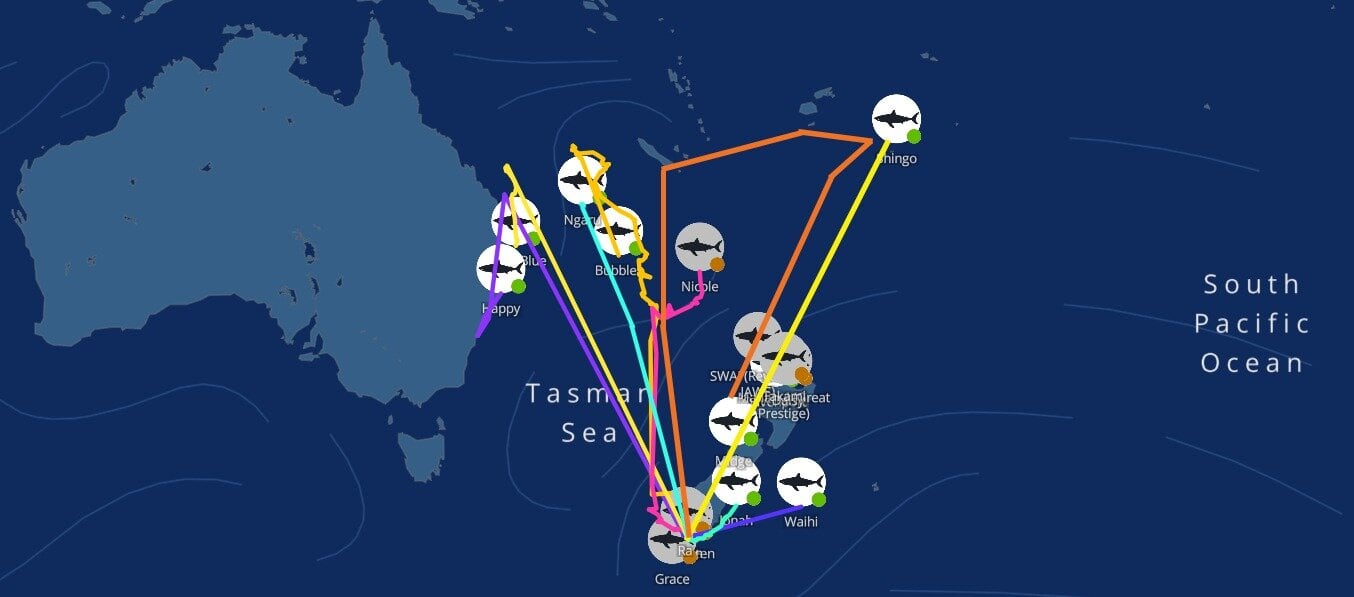

Data from the public-sponsored satellite tags is displayed on a tracking app, which means people can track tagged sharks in real time.

The Department of Conservation (DoC) and local iwi have provided funding to continue the Great White Project in the 2025-26 season.

Elliott said his team had a “stellar” first season in the summer of 2022-23, tagging newborn to sub‑adult sharks amid consecutive summers of great white aggregation in the Tauranga Harbour area.

However, after the 2023 floods, satellite tracks showed that sharks left the Bay and did not return in 2024-25, prompting a strategic shift south.

Marine biologist Dr Riley Elliot was the executive producer and presenter of several series of the Discovery Channel's Shark Week.

“With iwi and DoC permission, we focused tagging at one of the most reliable great white aggregation sites on Earth: Motunui/Edwards Island, just north of Rakiura/Stewart Island,” Elliott said.

The site, last robustly studied by Niwa and DoC before 2015, sees great whites arrive each summer from across the southwest Pacific to feed, socialise, court and possibly mate.

Between April and May this year, Elliott tagged 15 sharks: males and females from 2.5m (around 5 years old) to 3.9m (10-20 years old).

Each now carries a satellite unit that pings a location when the shark surfaces, enabling real-time public tracking via the Great White App.

Sharks also have acoustic tags that can be detected for up to a decade by receivers across the Pacific.

DNA samples were also taken, with iwi consent, to contribute to broader population assessments.

The Great White app tracks as of October 2025.

As autumn set in, smaller, younger sharks were tracked leaving Motunui while larger, mature animals arrived and displaced them.

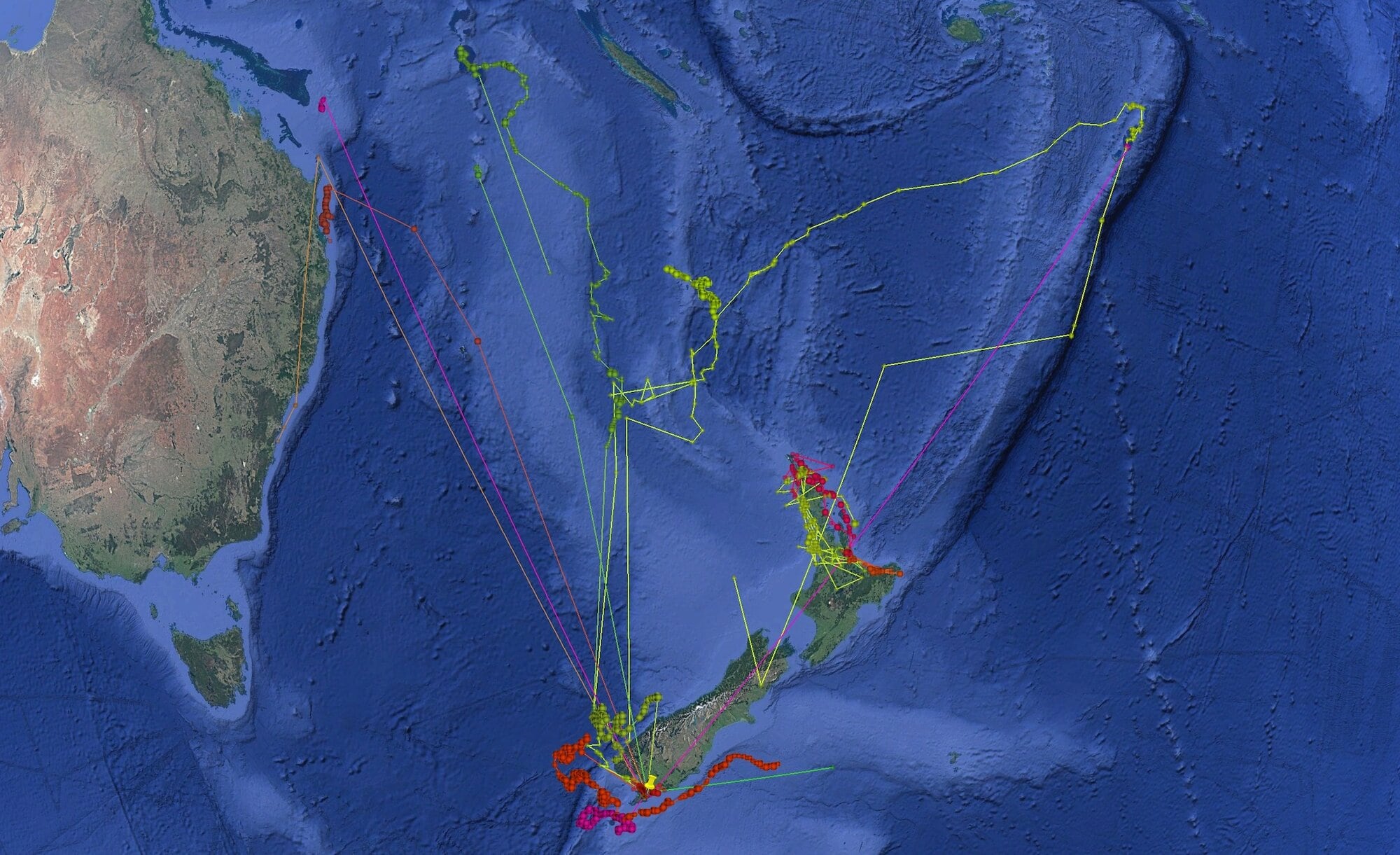

Elliott said many used similar “highways” north, moving off Fiordland, then spending weeks submerged before popping up further north in the Tasman Sea.

Temperature logs from surfaced tags showed dives into water as cold as 5C, consistent with depths approaching 1000m.

“The reason for these dives remains unknown,” Elliott said. “We think they may be using the seafloor and underwater currents to navigate.”

Several sharks headed northeast toward Tonga and were later reported by whale-watching guides in the Vava’u Islands.

“Great whites are rarely seen in the Polynesian islands, even though they spend half their lives there,” Elliott said.

The movements could have shadowed humpback migrations, offering opportunistic “blubber buffets” from whale carcasses, and thermoregulatory benefits for great whites, which are one of the few shark species capable of maintaining elevated body temperatures.

Tracking of great white sharks across the southwest Pacific.

Others tracked east to the populated coasts of Queensland and New South Wales.

“This was poignant to observe as it cemented the Anzac connection this population is built from,” Elliott said.

However, the tracking also raised alarms.

He said while great whites were protected in Australia, state-level shark nets and drumlines (traps) had been operating since the 1960s, and several New Zealand-tagged sharks had surfaced near these devices.

“It was unfortunate that several tags came off and began floating down the coast,” Elliott said.

The tags were designed to be minimally invasive, held in place by a dart that would eventually eject like a splinter.

One tag that washed ashore on the Gold Coast was photographed by beachgoers within 20 minutes and flown back to New Zealand the next day.

A tag found by lifeguard nippers on Australia's Gold Coast.

Another unique track, of a large female named Grace, headed south to the Snares Islands rather than north. Shortly after, her tag came off in a zone heavily fished by squid trawlers.

“Overlaying commercial fishing effort and bycatch rates of great whites, a sad reality was suggested – the gauntlets these and all marine creatures run when moving through the ocean: nets and hooks.”

Elliott said about 15 great whites were reported as bycatch in New Zealand fisheries each year, with a similar number deliberately killed in Australian shark nets and drumlines.

“These animals are supposed to be protected, yet we are letting them down.

“Recent estimates suggest there may be only about 200 mature, mating individuals in this whole population.

“We cannot afford to lose them – they dictate the health of the marine ecosystem.”

He highlighted South African waters, where great whites had almost vanished; in their absence, seal numbers exploded, overgrazing fish stocks, and contributing to kina barrens: marine deserts in which overabundant kina have devoured kelp forests.

Riley Elliott with a great white shark on Discovery Channel's Shark Week TV series.

Shark safety tips for summer

Elliott urged beachgoers not to fillet or dispose of fish near swimming areas and to avoid swimming where berleying or fishing was taking place.

“Overlapping with feeding sharks is a recipe for mistakes,” he said.

Sharks were “incredibly well‑behaved predators” that generally avoided unfamiliar situations.

“We overlap with them regularly, and they do their thing while we do ours. The risk of adverse interactions is incredibly small and can be well mitigated.

“Common sense enables us to enjoy the ocean this summer and allows sharks that come close to shore during this season for pupping and mating to do their thing and ensure the next generation of animals that help maintain a healthy ecosystem.”

Public invited to sponsor tags, follow sharks

With the 2026 season about to kick off, Elliott invited public sponsorship to expand tracking.

Satellite tags cost $4300 and allow donors to name a shark and follow its movements via the Great White App anywhere on Earth.

Acoustic tags cost $800 and enabled long-term monitoring of a named shark, he said.

To sponsor a tag, email sustainableoceansociety@gmail.com.

Ayla Yeoman is a journalist based in Tauranga. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree majoring in communications and politics & international relations from the University of Auckland. She has been a journalist since 2022.

0 comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.